Small Craft

Late 19th & Early 20th Century British Yachting

The Sailors: Amateur British & Irish Yachtsmen Before World War One

An Historic Fragment by Herbert Knight.

Illustrations by Donald Maxwell

"WANT a boat, sir?"

"No, thank you!"

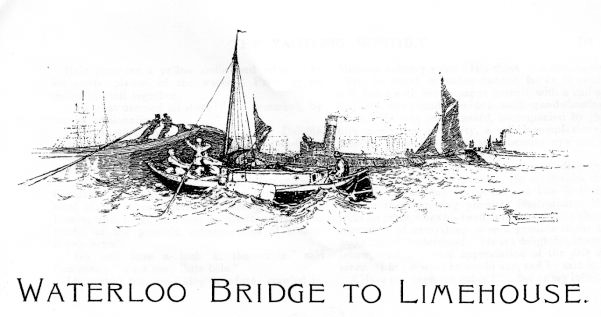

We stood on the wooden float at Waterloo steps gazing out into the river - I at the Dolphin, a 20ft. boat of nameless rig with bright green lee-boards and brown canvas, the man at nothing in particular.

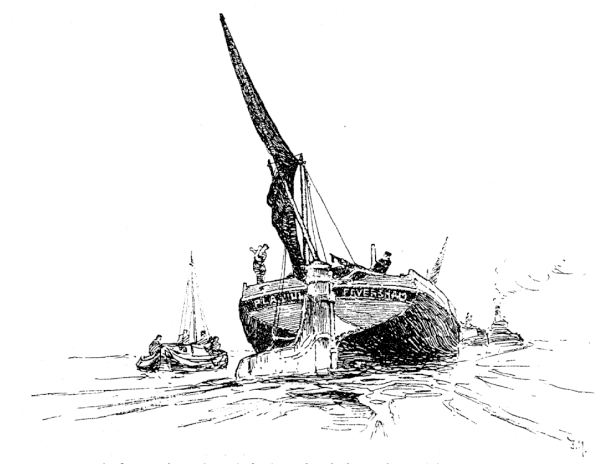

The Dolphin had once been a Dutch police-boat, and Malcolm, her owner, a queer artistic genius with distinct tendencies in the direction of vagabondage, had picked her up somewhere in Holland and rigged her to his own ideas - ideas which, at one time or another, had attracted the attention of every riverside wit from Teddington to the Nore.

I watched anxiously for some sign of life from her interior, the man who had accosted me standing meditatively by, waiting events.

Much as I dislike anything that is likely to attract attention to myself, I saw clearly that unless I were prepared to stay where I was I must hail her, so, dropping my bag and umbrella, I shouted "Dolphin, ahoy!" with all my might. It was a miserable effort, my voice breaking on the "hoy" and tailing off into a frenzied shriek.

The man looked at me inquiringly, but, seeing my confusion, turned and spat sympathetically into the river.

"Don't seem to 'ave 'eard you, sir," he remarked, gazing with great earnestness at an ex-L.C.C. steamboat moored in mid-stream.

"It's the other!" I murmured feebly.

"The barge?"

"No, the other!"

"Oh!" There was a pause. Presently an idea appeared to strike him. "What did yer say 'er name was, sir?"

"Dolphin!" I replied laconically.

"I'll give 'er a hail." He did; the arches of the bridge rang with it; several people ran to the parapet and looked over. The Dolphin gave an ecstatic lurch as if in recognition of her name. I saw a head bob up from her bowels; it was Compton's. The head vanished, then reappeared, followed by a body, which proceeded to drop leisurely into the dinghy, and in a few minutes Compton was at my side.

I tumbled into the little nutshell of a craft, my bag and umbrella were tossed in after me, and, with a few words of advice from the man, we put off, Compton sculling for all he was worth to get out into the stream before the lively inflowing tide carried us beyond our objective. We bobbed about like a cork, and I began to regret my precipitancy in accepting Malcolm's invitation to spend a week-end in dropping down the river.

Genius has immortalised the Thames; but always from bridge, barge, or embankment, possibly because genius has a queasy stomach. There is nothing more disconcerting than to be in a small boat on a making tide held back by a stiff breeze, with tugs churning the ochre-coloured waters into a miniature sea.

As we reached the Dolphin's side a man crawled hastily out of the cabin and hung over the opposite side. His complexion was grey-green, and his whole demeanour one of acute misery.

"Hale, this is Knight," said Compton, by way of introduction. "Hale is a certified master-mariner," he added to me aside.

Hale gave me a yellow smile and returned to his contemplation of the water. Presently he pulled himself together.

"It's that damned oil-stove!" he remarked, by way of explanation.

I was anything but reassured. If the Dolphin and the oil-stove between them had produced this effect upon a certificated master-mariner, what earthly chance had I?

"Malcolm'll be aboard soon," volunteered Compton. I nodded and strove to get to the windward of the stove, but it was stronger than the breeze, and I had recourse to short, sharp sniffs, fearful of the possible consequences of a long-drawn breath.

"Go and have a look at the cabin," said Compton; "it's a cosy little hole."

I hesitated, but, not liking to refuse, crawled in. I remained just long enough to get a general impression of a contusion of blankets, clothing, tinned foods, and bilge-water, then baéd out with great suddenness.

"Snug little place, eh?" Compton's conversational efforts are frequently ill-timed. He is devoid of tact, and there are moments when I pray that his lips may be sealed with a great silence.

Delightful!" I responded, swallowing with great rapidity.

"Is the stove all right?" he persisted.

"It's going strong," I jerked out between my swallows.

There was a pause, then Compton appeared to realise the responsibilites of his position.

"Have something to eat," he urged hospitably; "there's boiled beef, ham, and sardines."

At this moment there was a hoarse yell from the landing-stage. I recognised with thanksgiving Malcolm's cheery voice. His shout is unmistakable. There he stood, or rather danced, for he is never still, laden with brown-paper parcels, with a coil of half-inch rope round his middle, smiling and shouting at us. He was soon aboard, accompanied by the fifth member of our party, a sallow-complexioned medical student with an apprehensive eye and a deep distrust for everything aquatic.

The humour of the river is both personal and peculiar.

It is cumulative in its action, beginning with the tugmen...

"Have you seen the cabin?" But to my infinite relief he ran on, "What do you think of it? The wind's failing; still, we'll drop down on the ebb. There are always the oars. So glad you've come!"

He seemed to infuse energy into all of us as he turned to the business of the day. First the parcels had to be stowed away; then there was the anchor to get up and sail to set. A lighter drifting down broadside on had to be avoided, and the lighterman's furious invective parried and personality met with personality. At last we were off. It is no easy task to take a small sailing-boat down river on a swift-running ebb with a failing wind, or a wind that has failed. It is a mad jostle of tugs with their strings of craft in tow, barges under their own sail, which the wind refuses to fill, and those irresponsible terrors of tidal navigation - drifting lighters.

Malcolm stood, tiller in hand, conning the boat, whilst the rest of us were lumped together amidships. I saw from our commander's look that he did not like the trim of his craft.

"Knight," he called out solicitously, "you go and have a lie down in the cabin, and don't forget the stove."

I resented being looked upon as ballast, yet obediently crawled through the narrow doorway. The cabin's dimensions were: Length, 8ft.; width, 4ft.; height, 3ft. l0in. It was a place into which no conceivable stress of weather should drive a sane and healthy-minded man. Along the centre was a narrow channel, devoted to bilge and other waste products, such as boots, collars, and sardine tins. It was not comfortable, I concluded, as I sat eyeing my natural enemy with helpless malevolence.

"Don't forget the stove!" Shall I ever forget it?

After a time I bethought me that perhaps it had been ill-treated, and was better-intentioned than appearances indicated. It should have a fair chance. At first I turned the wicks up higher, vaguely remembering that when turned too low they have a tendency to smell; but the choking black smoke which proceeded to lick round the sides of the kettle soon caused me to lower them again with great precipitation. Then I turned them down to the glimmering point, but without result; so cursed the unholy thing with great energy and gave up the unequal contest. I lay down upon the clothes, blankets, and tinned provisions, hoping that we might run into something, be rescued and taken to a hospital, where the cooking was done by electricity.

Feeling a crisis approaching, I crawled out and posted myself by the starboard gunwale, carefully avoiding Malcolm's eye. By great good luck he gave an order for us to get some way on the boat with the oars, for the wind had failed entirely and we were between two strings of barges. I grasped an oar and proceeded to pull as if my life depended upon it. We were knocking about abominably, and little sportive waves broke over the side, wetting me through from the waist downwards.

To add to my discomfort there was a ceaseless fire of chaff from the barges and tugmen, who seemed to find in the Dolphin a butt for their wit. She is rather odd in appearance, I confess, but not to the degree justifying these masters of craft in their strictures.

...And running the whole length of the string of barges.

That journey down the Thames! It haunts me still. Tired, depressed, ill, with no thought of anything but how to get away from the reek of paraffin oil. The beauty of the river, with its ever-changing face and features; the glorious sky effects; Somerset House and St. Paul's, grey and majestic; the tangle of shipping in the Pool - all were obliterated by a little oil cooking-stove. How many times I swallowed during that journey I shall never know, my throat positively ached with it; but it was my refuge, and I tugged at my oar and swallowed, swallowed, and tugged at my oar. Like galley-slaves we pulled, trying to persuade the phlegmatic Dolphin to answer to her helm. At last we reached Limehouse, where some tackle had to be shipped. To my infinite relief it was decided to spend the night there, and we warped in behind the pier and had tea.

After the meal Compton and I were left in charge as an anchor watch. For an hour or more we sat smoking in silence, watching the lights of the river one by one springing into being as the twilight deepend into night. Slowly the tide receded, leaving us embedded in a black mass of slime. It was an unsavoury hole that we had selected as an anchorage.

The last glimmerings of twilight had faded before we heard the expected hail from the pier. Five minues later there came another hail, this time for a rope, the dinghy was fast in the mud. We could just see her in the darkness. After several fruitless casts Malcolm caught the line, black with river mud, and we drew the little craft alongside. Stanton was the first to get aboard.

"Good God, man! What's the matter?" I ejaculated on catching sight of him.

There was a supressed giggle from Malcolm. Compton laughed outright - an insulting, jeering laugh. Stanton, quite unmoved, proceeded to divest himself of a pair of water-wings, purchased and donned as a precautionary measure.

"Malcolm, don't forget my bananas," he called out.

The man had been ill and his nerves were out of gear. He was for ever offering some word of advice or warning. Now he had purchased water-wings! I could see Compton's lips moving, and his hands worked ominously. Compton positively detests Stanton.

As we shipped the last of the tackle and a few luxuries in the way of fruit and cakes the rain, which had been threatening all day, began to drop in steady earnest, driving us into the cabin. A joint of boiled beef was produced wrapped up in a newspaper, a loaf of bread was discovered beneath a pillow, a knife rescued from the bilge-water, and we set to work hungrily. Compton and the oil-stove between them succeeded in producing coffee, and our feast was complete.

Suddenly Stanton's voice was heard inquiring for his bananas. Compton stifled a curse; Malcolm grunted.

"I know I brought them in here," Stanton proceeded. "Do look, Malcolm."

Malcolm ferreted about, and presently sat up, drawing from under him a brown-paper bag.

"I'm sorry, Stanton; 'm afraid I've been lying on them."

"On my bananas?"

"Oh, they're all right!" continued the genial Malcolm imperturbably.

He tossed the bag over, and Stanton gazed at the pulpy mass in tearful despair. Compton settled the matter by tossing the whole overboard.

At eleven o'clock our skipper suggested turning in. The cabin was, as has been said, exactly 8ft. long by 4ft. wide, with a height, scarcely equal to its breadth. On each side was a narrow mattress upon a raised platform. Malcolm and Stanton took one each, whilst I curled myself up at their feet, compressing my 5ft. 10in. into the 4ft. of space available. Compton preferred sleeping out in the rain. Compton has odd tastes.

For five hours I lay, with the rain blowing in upon me through the open door, listening to the sounds of the river. The tide was making now and soon lifted us off the mud. Then it was that the dinghy, rendered lively by the swell from the never-ending procession of tugs, began pounding against our quarter. Sleep was at first out of the question, and I fell to watching the lights and listening to the shouts of the crews of ocean-going boats crawling up stream to their moorings.

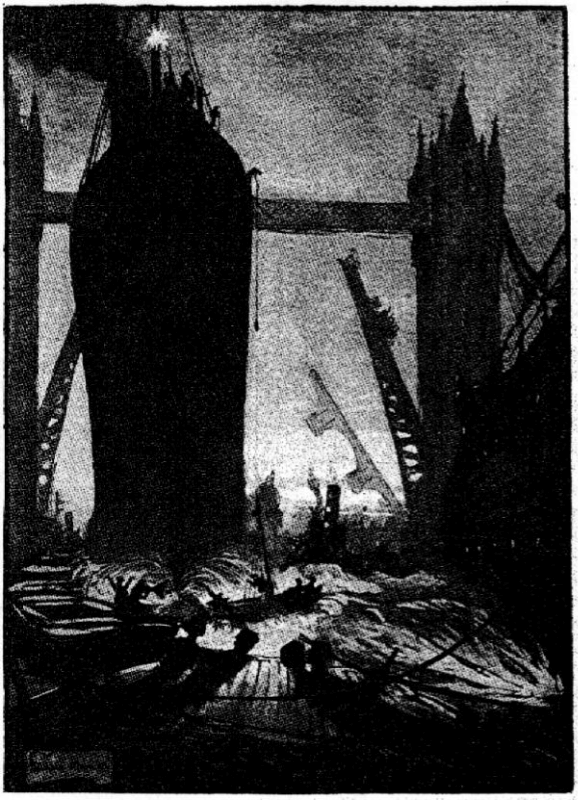

Eventually I dozed off; but even then the Dolphin did not forsake me. Soon we became involved in a situation of such horror that no pen can describe, and only an artist of inspiration and unsteady habits can depict. I awakened just as an omnibus came crashing down on our deck - it was the dinghy pounding at our side.

A Nightmare of the Tower Bridge.

At about nine o'clock a disreputable figure carrying a bag and an umbrella might have been seen toiling through the drowsy streets of Limehouse. It had not washed since noon of the previous day and was heavy for want of sleep.